The trams that built Wellington

Which year saw the most public transport passengers in Wellington’s history? You might think 2019, before the pandemic put public transport in crisis. Or maybe 2024, as our bus lines benefitted from more dedicated lanes.

The answer is 1943.

That year, Wellingtonians took over 64 million tram journeys in Wellington City alone. That doesn’t even count trains. Today, we only manage 37 million journeys across all buses, trains and ferries combined. That’s with a population four times the size.

1943 was a Wellington transport nerd’s dream because electric trams crisscrossed our city streets. They ran every 10 minutes, offering women, children, the elderly, and workers a way to traverse a growing city efficiently.

It has been a long time since the trams traversed our town. The history of our tram system and its demise is complex and gnarly. Politics, lobbying, regulation, changing attitudes to transport, even World War II played a part in its downfall.

Passionate people across the world are demanding tram tracks return to their streets. Trams and light rail are coming back in cities sick of the unsustainable land-gobbling nature of car-based planning.

Wellington can and should bring our trams back. Done right, it could make our public transport the best way to get around, full stop. It could help us in the quest to slash pollution, and help more people live in our central city without it costing the earth.

Our city holds traces of an extensive system built quickly to support a rapidly growing capital. In the first of a two part series, we’ll explore the bright and vibrant history of the tram lines that made Wellington, and why we lost them.

Wellington grew along the tram lines

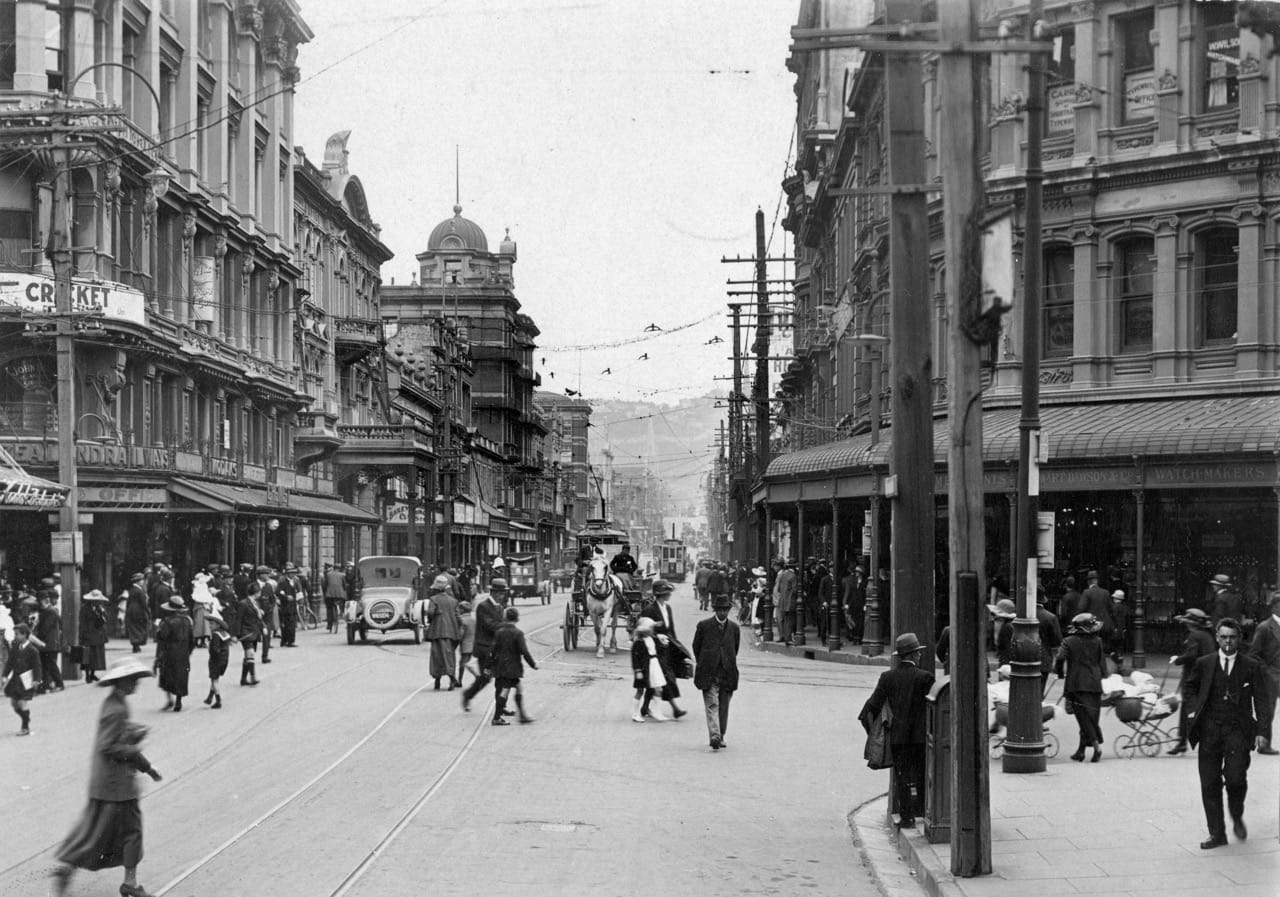

The colonial settlement of Wellington was shaped and propelled by tramways from as early as 1878.

Private companies laid tracks along streets to carry more people efficiently as the city rapidly grew. At first, the vehicles traversing our terrain were pulled by horses. Steam trains were trialled but weren’t beloved by people living in the city. The noise, pollution, and the tendency to scare the shit out of horses was a PR nightmare. Steam lost its steam… but the colonial council saw an opportunity.

Growing the city couldn’t be done on horseback alone, and there was farmland to the south and east which could house more Wellingtonians. They just needed transport connections. There was an opportunity to use newfangled electric trams to bypass the need for hooves and offer a great way to move many people from work and home.

It just so happened that running an electric tram service could be a fantastic money maker for the Council too. Some believe that’s why the Council chose wider tracks rather than the narrow tracks our trains run on. If they had chosen the same tracks as trains, the trams could have been nationalised, and the Council would lose revenue.

In 1902, Wellington City Council purchased the existing tramways, and started building a network of electrified trams that expanded from Karori to Seatoun, Island Bay to the Railway Station.

The age of electric tramways in Wellington had begun.

The system was built at pace. Workers laboured under backbreaking conditions from 4am to 11pm every day to lay tracks along Cuba Street, Courtenay Place, the Harbour Quays, and more.

The rapid and gruelling rollout delivered a 10 minute tram service from the railway station to the Basin Reserve two years after the Council approved it.

More lines were built in quick succession. They connected Lyall Bay, Brooklyn, and Northland. Tunnels were carved into the maunga surrounding the central city, which we still depend on for buses and cars today.

The city grew quickly with the investment. More people started neighbourhoods connected by frequent tram service, and came to depend on them for everything.

Trams shaped daily life in ways that are hard to imagine now. When rugby games were held at Athletic Park in Newtown, special trams queued to ferry thousands of fans home. The trams ran so frequently you never needed to check a timetable. Women, children, and older people benefited from a system that could move them around the city at modern speeds.

On average, a Wellingtonian in 1943 would take 521 tram journeys annually. Today, the average Wellingtonian takes 71 journeys across all forms of public transport. The capital used to be a public transport darling. Today, it is woefully car-dependent.

What changed?

The death of trams

Our tram lines were first neglected, then shrunk, then closed all together. World War II rationing, car advertising and suburbanisation all contributed to the decline and disappearance of the tramways.

World War II was a double-edged sword for our tram system. When New Zealand was fighting the Nazis, resources were in critically short supply. Citizens rationed the basics like food, and commodities like rubber, steel and precious fossil fuels were constrained to put everything we had into manufacturing army tech.

The rationing was a boom for tramways. Trams caused less road wear than cars, ran efficiently, and didn’t need tyres. People were pushed to leave private vehicles at home and take the tram instead. 1943 was the peak of the tram system for a reason: the war constrained resources.

That rationing also had a corrosive effect. Every scrap of steel needed to be put to the war effort, meaning that once the war was over, the tramways were in a sorry state. Lines were degraded and desperately needed repair.

Everything else in the economy was also screaming for maintenance. The bills were stacking up to build and repair neglected infrastructure. So leaders had to make a choice: restore the tram system or let it wither and die.

A street fight was brewing, and tramways were caught in the crossfire.

Streets have always been a point of contention in modern cities. Where people can and can’t be is about as political as it gets. For a while, roads were the domain of horses and humans, cars and carriages. That was changing, with more space being offered to faster, more dangerous vehicles.

Giving more street space to vehicles brought wear and tear, and annoying policy choices meant tramways got the short end of the stick. The Tramways Corporation was responsible for maintaining the roads around the lines, just as much as the steel they actually used. More cars on more streets meant more wear on the roads that the tramways had to repair, while losing revenue as passengers switched to cars.

Some drivers hated waiting behind trams when they stopped for passengers. Lobby groups for oil companies and car manufacturers wanted cars to get top priority, rather than the systems which carried 100x the ridership per vehicle. If cars had to slow or stop, how could manufacturers advertise the dream of speed?

All that lobbying was working worldwide. In the States, cities like Los Angeles were ripping out their tramlines and demolishing iconic buildings in favour of car parks. Trams were presented as old fashioned, from a bygone era that technological advancement has left behind. Wellington did the same: banning central city housing and incentivising suburban sprawl along the Hutt and Kāpiti Coast, designed to be driven.

The council had made its choice: rebuild Wellington for tyres, not steel wheels. Lines closed to make way for cars along tram tunnels. Rail was demolished to build the airport. Trolleybuses were used instead, even though they were far less popular than trams. Passenger numbers plummeted and have never again reached their peak. Meanwhile our carbon pollution started to rise and rise and rise.

The shift to car-dependent planning didn’t just increase pollution. It also locked out entire groups of people from taking part in our society. By choosing to build our city around a mode designed to serve working-age men, it denied women independent transport, it deprived children a community play space, and it deprived the elderly of social connection unless they could drive.

To this day, trams offer agency to people left behind by cars. Modern trams offer quality journeys to our disabled, our children, and our older generations. Yet, we’re investing billions into entrenching a car-focused system that reduces the independence of those groups. Meanwhile, projects to make other methods of transport as appealing as cars are cut and delayed, even under Labour and Green local leadership.

As the last tram in New Zealand departed to Newtown in 1964, Mayor Frank Kitts expressed a nervous feeling that maybe our city would regret the loss of the tramways. He was right.

Almost as soon as the trams were ripped from their lines and asphalt covered their tracks, the English speaking world realised that more lanes don’t solve traffic. It turns out the trams did more than keep our pollution low and our communities connected. They were also congestion-killers. And we had just mothballed them.

Though Wellington has forgotten its golden age of trams, their traces are all around us. When people take the bus to the airport, they’re using a tram tunnel. Wallace Street is a gentle grade because tramways ran along those lines. There are intricate bus stops in Oriental Bay because the trams took people to the beach. Some of the rail remains, buried under asphalt and bitumen.

The trams offered an alternative to many who, by age or circumstance, could not or did not want to drive. We lost a system that can help move us around without costing the earth through ever growing pollution and sprawl.

Wellington is still set up to restore a world-class tram service like you’d find in Europe. We are a tight-knit, compact city designed for trams because we were built by trams. Our streets are dormant, waiting for rail to restore them to their former glory.

By bringing back a modern tram system, we can improve our transport and make Wellington a modern, bustling city of the future.

In part two, the vicious fight to bring trams back in cities worldwide, and how Wellington could take note from an innovative German city to make the most of a new tram system.

Sources

This was only possible with fantastic sources like “Wellington Tramway Memories” by John William Frank Lawes and Graham Stewart’s “Around Wellington by tram in the 20th Century”. On top of that, the City Archives provided fantastic insight with tramway annual reports. I’d thoroughly recommend setting up time with them once they’re moved into Te Matapihi.