Wait. Is AI fuelling the climate crisis?

AI feels like it’s taking over the world. The government is trying to make its own ChatGPT service. AI is enshittifying the internet. The new iPhone’s biggest selling point? AI.

It has grabbed the spotlight. Has it also fuelled the climate crisis?

The answer is complicated. It’s also a fascinating way to understand how, in the context of climate change, big numbers aren't always what they seem.

How does AI work?

I’m not an expert, but I can give you a basic rundown. Artificial intelligence (think products like ChatGPT and Claude) is made by hoovering up tonnes of data and running very complex programmes to make connections between those data points. Get a big enough collection of information (like, for example, everything on the internet) and you can build a computer programme that can write you emails or generate emoji based on what you describe.

The big AI products run in data centres: buildings with loads of high powered computers that operate the internet. Search something in Google or ask ChatGPT to come up with a travel plan, and you’re sending your question to a computer in a data centre which processes that question and sends you the answer.

Data centres are why AI can be associated with the climate crisis. AI runs on electricity.

How does AI contribute to climate change?

Unfortunately, I can’t find research that shows AI-specific pollution data, but we can use research on data centres to get a general idea. Data centres power more than AI: they operate everything we do on the internet. Google Drive, Netflix, iMessage, the Spinoff homepage: all run by data centres.

Data centres pollute the world in two ways: their construction and their power consumption. At the moment, data centres use 340 terrawatt hours of electricity every year to run. They were responsible for 330 million tonnes of pollution that warms the world in 2020, and that is growing.

It is expected to rise to approximately 600 million tonnes per year in 2030. About half of that is from electricity, and the rest from building new centres to meet demand.

Here’s the problem. Those numbers are both big and small.

The perennial challenge of talking about climate change is that all the numbers are objectively big, but it’s hard to tell which ones are comparatively big.

For example, 200 boxes of Weetbix is an objectively large amount of Weetbix. But 200 boxes of Weetbix in my bedroom is very different to 200 boxes of Weetbix in a supermarket. The size of the number has to be judged by the context it sits within.

The context behind AI and climate change is that data centres are a tiny portion of the world’s pollution and electricity usage. 340 terrawatt hours of power is less than the world currently uses to power household lightbulbs. Everything you do on the internet runs through data centres, and those buildings use just 1.3% of the world’s electricity.

The pollution that data centres create is 0.8% of the world’s pollution. Let that sink in. As a species, we create so much pollution that 300 million tonnes of it is not even 1% of the problem.

Let’s say, that by some miracle, by 2030 the world cuts its annual pollution by 20% and at the same time data centres double their pollution. In that scenario, data centres would still only be 2% of the world’s annual pollution.

In short, data centres are responsible for a huge amount of carbon, but a tiny amount in the context of the world's climate challenge.

So… should we care about the climate impact of AI?

It’s complicated. I have really mixed feelings about AI. I think it’s completely reasonable for people to dislike it.

However, I don’t think that climate communicators and advocates should spend significant effort focusing public attention on stopping AI in the name of climate action.

Instead, we need to focus on what makes AI contribute to climate change in the first place: electricity.

New Zealand is fucking weird on the world stage because our electricity is almost entirely renewable. It’s easy to believe that most of the world is like us: powered by dams and wind farms and solar panels. I wish that was true, but the rest of the world is woefully fossil fuelled.

61% of the world’s annual electricity is still made by fossil fuels. Coal still generates more electricity than all the world’s solar panels, wind farms, hydro dams and other renewables combined.

Then consider that electricity is not all the energy the world uses. Loads of things, from steel mills to cars, use fossil fuels like petrol rather than electricity for energy. In fact, electricity powers less than 20% of the world’s energy. The vast, vast majority of the world’s energy is made by burning expensive and deadly fossil fuels, even in New Zealand.

We need to electrify everything that needs energy in the next 25 years. Some will argue that AI's surging power demand makes that a lot harder. The reason why is understandable: all that extra demand means new renewable electricity will be used for growing power capacity rather than replacing fossil fuel plants.

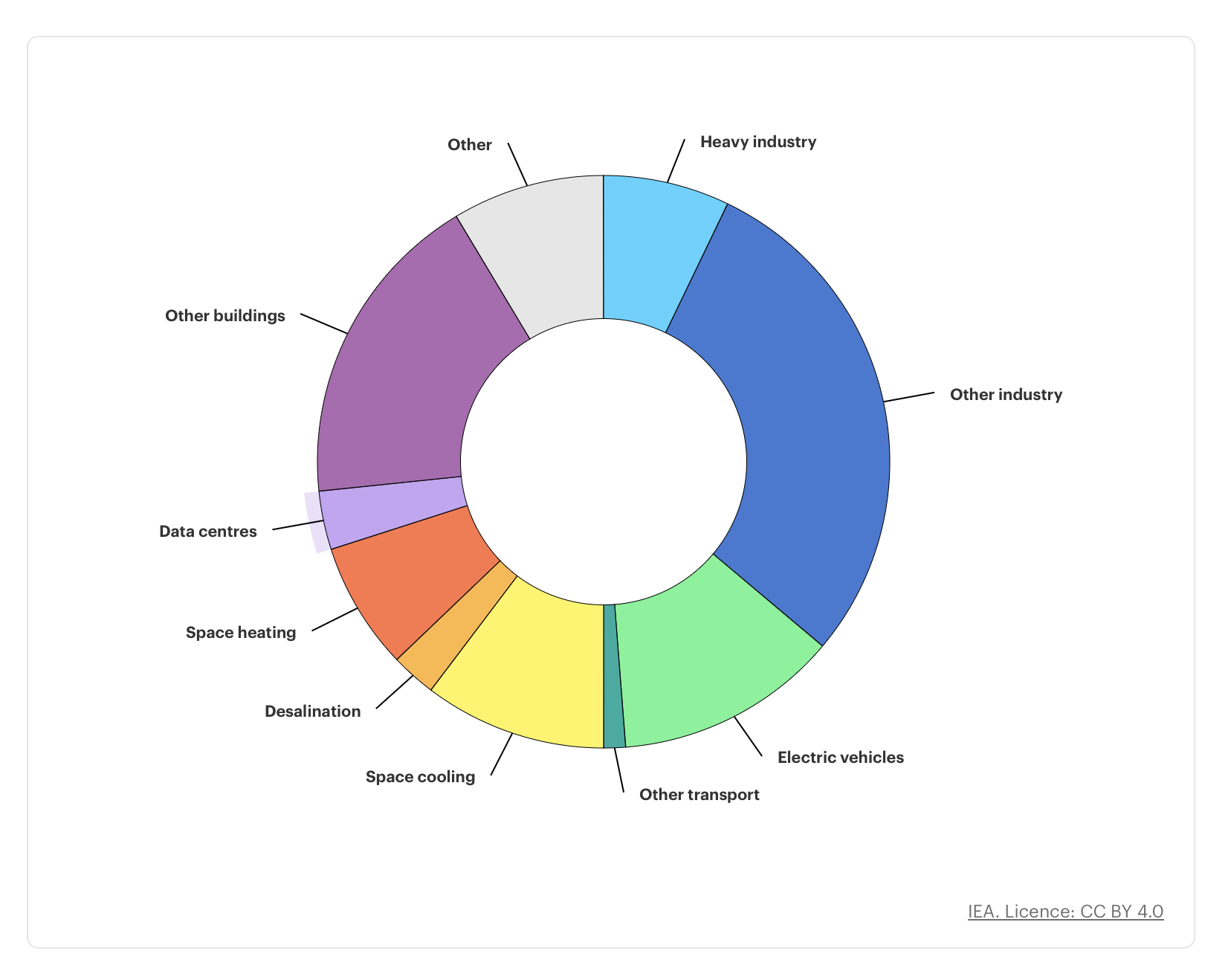

Thankfully, AI's power growth is still a tiny amount of the expected growth in power demand over the next five years. The challenge of surging electricity demand is coming from the absolutely necessary electrification of cars, industry, and buildings.

Artificial intelligence poses serious challenges to society. But if we put a stop to AI right now, it would not solve climate change. Not even close.

If we want to stop warming the world, the top priority needs to be replacing all coal, oil, and gas with renewable electricity as fast as possible.

Because, as always, fossil fuels are the real fuel behind the climate crisis.