Why trams should rebuild Wellington

It's a modest Monday morning in 2035. Derwent Street is glistening in the drizzle. You walk through your apartment block's central courtyard and out towards the Parade in Island Bay. It's time to catch the tram to work.

With a brisk pace, you get to your stop right as the tram to Johnsonville departs. No worries. The board says another tram will be here in just a few minutes.

The next tram arrives. Petone is the destination. People get right on – level entry has made boarding a breeze by foot or by wheelchair. The bell tolls and it slides away down steel lines embedded in the road.

The city is a fantastic backdrop as you read your book. Trees and apartment blocks dotting the streets. It's almost a shame the trams aren't a bit slower, because you love doing things and watching the world go by during your commute. Within 20 minutes, you’re at work. Since the tram upgrades, the streets of central Wellington feel alive again.

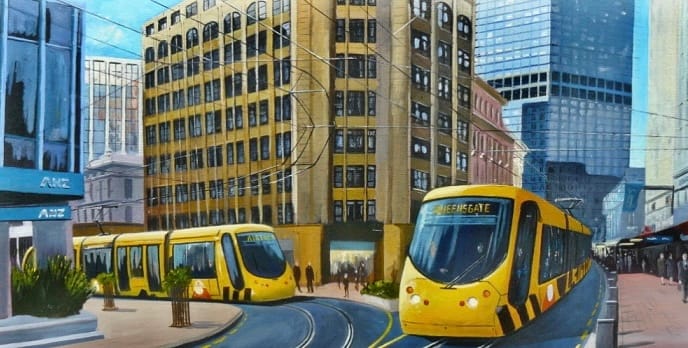

Trams are our future. These low carbon rides blend the best of buses and trains. When cities implement trams well, they can unlock astounding benefits for housing, streetscapes and quality of life, all while lowering transport pollution.

Light rail transit is resurgent across the world. Wellington was built by trams, and can be rebuilt by trams. By building a system that integrates our trains and trams, we could get most of the Wellington Region riding rail for work and play.

Reimagining the city with rail

Trams transform streets and cities for the better. You can see what I mean when we compare Melbourne's Bourke Street to Lambton Quay.

Melbourne's tram system runs frequently through the pedestrian area, but that doesn't dissuade tourists and locals from enjoying the streetscape. Buskers perform, people take photos, brunch groups dine outside. The tram lane feels like it’s blended into the civic space, rather than slicing through it.

Lambton Quay should attract people like Bourke Street, but the streetscape is holding it back.

Tens of thousands of people travel Lambton Quay each day on foot, but most of the street is dedicated to roads. Buses and cars pass through, polluting with noise and fumes. The road splits up the public space, whether there’s a bus going past or not.

Just imagine if Lambton Quay was cobblestoned and trams ran through instead. Wellington would have an abundance of bright, vibrant street space that everyone could use, while still moving many people.

The same goes for Manners Mall, which used to be a pedestrian mall. When public transport was diverted through it, walking space suffered to make way for a road. The Harbour Quays, Taranaki Street, Courtenay Place: trams can transform these areas into destinations worth enjoying, while carrying substantially more people.

Because rapid transit like trams move so many people efficiently, it unlocks significantly more housing. Trams can carry twice the number of people per hour as a bus lane, and nine times what a car lane can. If people don’t need to store cars to get around, you can use more space in the city for modern, high-rise housing. Car parks become community spaces.

With trams, Wellington could easily host thousands more family apartment blocks in Mount Victoria and Island Bay. That level of housing growth in our city could make central city living far more affordable for families.

They are also more accessible for people with different abilities, and cause less motion sickness than buses. They cut noise pollution and tyre pollution on top of carbon pollution. The average tram in the UK emits 29g of pollution per kilometre, compared to 170 grams per petrol car and 97g for the average bus.

It’s no wonder that trams appear to have a higher cultural appeal than buses, too. Transport advocates have found a rail bonus, where the permanence and perceived quality of ride mean that trams attract more patrons than bus lines of similar speed and frequency.

Trams would be a serious upgrade to our central city. We’re already built the city around rail lines. In order to have more people living affordable, low carbon lives here in Wellington, we need the capacity and good vibes of a tram-based public transport network.

With good planning, they can even solve our regional congestion problem. Most car traffic comes from outside Wellington. Instead of spending billions to make driving more attractive to the detriment of public transport, we could be bold and connect our tram lines to train lines.

The tram-trains of Karlsruhe

Local advocates Brent Efford and Demetrius Christoforou from Trams Action introduced me to a German model that would turbocharge the effectiveness of future tram lines.

Karlsruhe, in southern Germany, is iconic for inventing the idea of a tram-train: a system where trams can travel on street tracks and regular train tracks.

Their city pioneered the model because their railway station only reached the city edge. Passengers needed to get out of trains and into something else to reach town. The inconvenience was preventing people from using public transport.

Sound familiar?

Faced with that challenge, Karlsruhe modernised its railways and redesigned the tram network so trains could run from the outskirts of town through the central city, without the expensive cost of tunnelling underground.

If we take inspiration from Karlsruhe, public transport would get a lot more attractive. Right now, if you live in Waterloo and work at Wellington Hospital, you take a train to the station, then a bus crawling through traffic. A tram-train could run door to door over rail, saving time and hassle.

The convenience of cutting a changeover matters. When Karlsruhe converted their lines to tram-trains, they saw the number of riders jump immediately. Their Bretten Line moved 2,000 people a day before tram-trains. Now, it moves 18,000 people a day. Having a truly transformative user experience will make a difference to our region’s congestion and pollution.

Tram-trains aren't suitable for every kind of city, namely huge cities like Auckland. Integrating street and rail lines is technically complex and doesn’t offer the same high speed connection that a tunnelled train line can. Different places have different constraints, which is why Europe has implemented many kinds of tram systems.

Wellington is similar to Karlsruhe in population, and we face similar issues like an awkward railway placement and too small a population for tunnelled trains. If Works in Progress is anything to go by, Wellington could fit the bill for tram-trains. Our public transport needs a serious upgrade to meet the ambitious and necessary goals to cut the region’s transport pollution. An integrated regional and city rail system could be exactly the solution.

Regardless of how we build trams, we have ample inspiration from across the world. While New Zealand bet the family silver on car-dominated transport, places like Germany and the Netherlands invested in rail. They’re leagues ahead.

Our transport system is begging to be redesigned to cut carbon and move more people than one more highway lane ever could. Personally, I love how tram-trains would offer a seamless commuter experience. For those currently using the motorway, it could relieve them of the eye-watering cost of car ownership.

To really deal with Wellington’s pollution, our city and national leaders need to offer transformative change to our streets. Trams can be that change.

Delightfully designed vehicles would free Lambton Quay and Courtenay Place to be vibrant public spaces, unlock tens of thousands of homes, and make for some sick souvenirs at Te Papa.

Investments like this are worth it. We shouldn’t be afraid to build infrastructure that cuts carbon across the region while increasing housing supply. A modern tramway system is that kind of infrastructure – one more lane on Vivian Street isn’t.

Anyone who has visited Melbourne or Amsterdam will know how much trams improve travel. I hope that Wellington is bold enough to transform itself around them.

In my third and last tram article, we’ll explore the political challenges. Sexy, I know.

Just three years ago Wellington was trying to build a tram-like system. When the Government changed, the project was promptly taken behind a woodshed and shot. Delays, uncertainty, and too many transport cooks in the kitchen doomed its existence.

To restore steel lines to our streets, we must finish our series with the hard political choices that must be made to make it real.